Explore the new exhibit at the Grand Center for the Arts and Culture in New Ulm, Minnesota, featuring the photographs of Edward Curtis. After the video, there is a link to virtual tour of the exhibit in the Four Pillars Gallery.

Explore the new exhibit at the Grand Center for the Arts and Culture in New Ulm, Minnesota, featuring the photographs of Edward Curtis. After the video, there is a link to virtual tour of the exhibit in the Four Pillars Gallery.

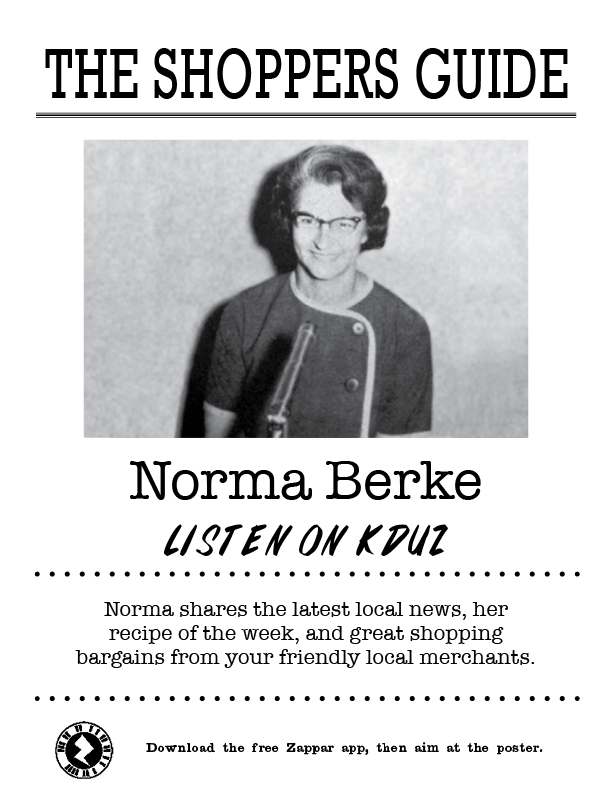

What are the best uses of augmented reality for interpreting the past? We created four interactive posters for the Litchfield Heritage Preservation Commission. First, you’ll need to download the free Zappar app to your smart phone — works with Apple and Android. Then, after opening, point at the poster and watch history come alive.

With virtual reality and augmented reality standing on the verge of popular adoption, this might be the Thanksgiving of the future. The technology, though, is advanced enough to make it inaccessible to small historical societies and museums. I saw two attempts this weekend. The Galena and U. S. Grant Museum promoted its holograms of Ulysses and Julia Grant — intended to serve as orientation. It was not a hologram, but a video projected on black curtains. The script also fell short, as the Grants explained what visitors would see in the museum, obviously not in character. Over in Dubuque, I visited the National Mississippi River Museum, a wonderful complex, where I watched a National Geographic film on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great story, although, as is often the case, the journey to the Pacific is highlighted and the return adventure barely mentioned. What interested me was that it was promoted as a 4D experience. Which it wasn’t. No 3D glasses. Instead, at key points, rumbles under the seats as a storm approaches, quick sprays of water in the rapids, and wind on the mountaintops. Interesting but a gimmick. So I’m not sure where the new technology will lead us in the field of history.

I will be participating roundtable discussion at the upcoming annual meeting of the American Association for State and Local History in St. Paul. “Interpreting Main Street” will look at the ways that four communities interpret their historic commercial districts. Although I’ll be representing New Ulm, I’ve worked with the other three towns: Red Wing, Willmar, and Winona. The other panelists each bring a different perspective to the challenge of creating a museum without walls.

Come join us. Friday, September 19, 2014 from 2:00 to 3:15 p.m. The conference will be held at the Crowne Plaza St. Paul.

It is early June as we approach the anniversary of one of those landmark dates in history that evoke deep memories for the oldest generation — June 6, 1944. Soon the events will be solely in the hands of historians rather than eyewitnesses. Recently I came across excerpts of CBS Radio reports on the invasion of Normandy. We know the end of the story — one that is often retold by historians. To hear it unfold is thrilling, with disclaimers from the announcers as they piece together information as it crosses the desk. I suspect, in today’s world, that we would be receiving immediate twitter accounts from the people of France. Of course, I still love to listen to baseball games over the radio, er, make that internet radio.

In his essay, “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James said that all writing has two parts: the idea and the execution. He wrote, “We must grant the artist his subject, his idea, what the French call his donnée; our criticism is applied only to what he makes of it.” For more than thirty years, documentarian Ken Burns has looked at American history through his lens. Through the 1980s, his vision of the past developed in films such as The Statue of Liberty and Huey Long, culminating in his breakthrough series, The Civil War. That is the idea. The execution has become just as well-known: the voiceover quoting period sources; the wistful, sometimes jaunty, often haunting musical score; and, of course, the pan-and-scan technique now known as “the Ken Burns effect.”

With the release of his iPad app, Burns tries to repackage the donnée, using technology that did not exist when he began filmmaking. Essentially, the iPad app is a collection of clips from past films, but arranged so the body of his work — thirty plus years of film — can interact in new ways. You can view them chronologically, through a timeline, or via a series of playlists each centered in a particular theme, like race or art. This breaks the narrative thread and places you in the realm of the donnée.

I’ve watched every minute of Ken Burns’s work — often multiple times — so I know the stories. What I can do, though, is follow the idea — race, for example — developed through each of his films. The app is enhanced by new video comments by Burns. In his films, you might watch the ideas develop over ten or more hours. I think of the issue of race, for example, as shown in the Baseball series. In the app, he hammers home the ideas in newly-filmed short clips — this is what I was saying. I can watch four hours of Mark Twain and, in the end, grow aware of how funny his writing remains. (Read Finley Peter Dunne to understand how unusual that is.) Here, Burns comes on and says that in a brief summary.

This is a worthy experiment. It would be interesting, in the future, to be able to easily compare other documentarians with Burns — how a single historical event might be viewed through different lights and shadows.

Clio and the Camera from DSTspring10 on Vimeo.

I’ve been thinking about form of the “modern” history documentary. The format that has come to dominate the field — certainly the PBS “American Experience” documentaries is the Ken Burns approach. It includes the use of historical photographs, using pan and scan, plus interspersed “talking heads” providing commentary or telling a story. This format has come to dominate the field — certainly the PBS “American Experience” documentaries.

I came across this interesting ten-minute survey of the history documentary, Clio and the Camera, completed by Andrea Odiorne, a student at George Mason University. It traces the changing styles of telling history via moving images, not only in format but also in technology. As someone who has created nearly 200 short form history documentaries — pastcasts — I wonder how the advent of the portable viewing device might change how the next generation documents history.

J. P. Maclean, a historian, set about researching the Shakers in 1903, traveling across southern Ohio. He wrote about his first glimpse of Union Village, a Shaker community located near Harrison, Ohio: “When I caught sight of the first house, my opinion was confirmed that I was on the lands of the Shakers, for the same style of architecture, solid appearance and want of decorative art was before me.” The University of Cincinnati, through their Center for the Electronic Reconstruction of Historical and Archaeological Sites, is doing some exciting work in using virtual reality to interpret history. Using tools like Google Sketch-up, students have recreated the exterior and interior of buildings in the Whitewater (Ohio) Shaker Village. While not the revelation that Mr. Maclean had, it opens a new perspective into the “land of the Shakers.”

CERHAS has used the approach to create a fascinating website about ancient Troy, complete with a virtual tour. Visit:

I’d like to see a historic downtown streetscape created for a Main Street Community.

The St. Paul Pioneer Press has a great story in today’s edition, with reporter Mary Divine looking at the city’s new podcast walking tour. City planner Abbi Jo Wittman said of the series, “From the city’s standpoint, they’re designed as part of the public-education program. They are a tool to help residents and visitors of all ages. I’ve already been contacted by a local teacher who would like to use them as part of a Minnesota history class.”

And Divine picked out a quote that summarizes my philosophy. “Each town has its own very interesting story,” [Hoisington] said. “You just have to listen a little bit, and it becomes evident what makes that town special.”

In May 1813 Jane Austen visited a retrospective exhibit of the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), England’s great portrait painter. That moment is now recreated in an online exhibition called What Jane Saw, one of the first great blockbuster museum shows.

It’s a great use of some new technology to give us insights into the past. The gallery, in a building that was subsequently demolished, was recreated using the 3-D modeling software SketchUp, based on precise measurements recorded in an 1860 book. This primary source material was a twenty page pamphlet that was sold during the exhibition, listing 141 painting. With this starting point, the researchers added narrative accounts in nineteenth-century newspapers and books, and precise architectural measurements of the British Institution’s exhibit space.

Now, what makes this so interesting? It provides relationships that a simple catalogue would not. For example, portraits of the prince regent and his mistress were discreetly kept apart. On the other hand, should we read anything into the portrait of George III hanging near the painting based on Shakespeare’s mentally unstable King Lear?

Of course, who can resist the Jane Austen connection? In a letter to her sister Cassandra, Austen joked how she would be searching for a portrait of Mrs. Darcy among these pictures.